If you're a member of the public, check out our public facing information about capsule sponge testing.

The capsule sponge, also known as ‘pill on a string’, has been developed over the last 20+ years by Cancer Research UK funded researchers to help detect oesophageal cancer and its pre-cursor condition, Barrett’s Oesophagus, earlier.

Late-stage diagnosis of oesophageal cancer is common, with diagnostic challenges including non-specific symptoms that overlap with more common benign conditions. If detected at an earlier stage, oesophageal cancer survival is higher, with 63% of people diagnosed at stage 1 surviving for 5 years or more

. Improving pathways to diagnosis, including identification of Barrett’s oesophgus, may have a positive impact on timelier and earlier diagnosis of oesophageal cancer.There are now several different capsule sponge technologies in use, including Cytosponge and Endosign. The device is used to sample cells from the lining of the oesophagus before they are tested for cell changes that may be a precursor to oesophageal cancer.

Capsule sponge testing has the potential to improve patient experience and endoscopy (including gastroscopy) capacity. Studies are underway across the UK to evaluate capsule sponge testing in different use cases.

For more information about the recognition and referral of oesophageal cancer, see our two-page oesophageal cancer insight guide for health professionals in England and Wales.

Read our guideThe kit includes a small capsule containing a sponge attached to a surgical string. The patient swallows the capsule, which dissolves in their stomach. The sponge is retrieved by the health professional after a few minutes by pulling on the string. As the sponge moves up through the oesophagus it collects cells from the oesophageal lining which are analysed by pathologists in a laboratory for markers of Barrett’s oesophagus or oesophageal cancer. The test can be performed by trained professionals (eg nurses) in a community setting.

Watch this video to see how the test is performed:

Capsule sponge testing may improve patient experience, which could reduce did not attend (DNA) rates along the pathway. Compared to gastroscopy it is less invasive, quicker, does not require sedation and can be performed in a community setting.

It can be performed by different types of health professionals, including doctors and nurses.

High levels of patient and clinical acceptability have been reported

,.Pilot results demonstrate the potential of the capsule sponge to reduce endoscopy workload, by identifying those at low risk of Barrett's Oesophagus or oesophageal cancer and removing them from endoscopy wait lists.

Capsule sponge has been reported as more cost-effective than standard care in evaluations.

Adverse effects have been reported, including abrasion, incomplete swallowing, sore throat and detachment of the capsule sponge.

Data suggest that Barrett’s oesophagus may be missed in 19-27% of those with a negative capsule sponge result

,. Safety netting those with a negative capsule sponge result but concerning symptoms is vital.The device is not designed to detect stomach cancers, which present similarly to oesophageal cancers and could be missed if follow up endoscopy is not indicated. There is limited evidence demonstrating that capsule sponge could be used as a tool to detect oesophageal cancer earlier or that it improves oesophageal cancer outcomes.

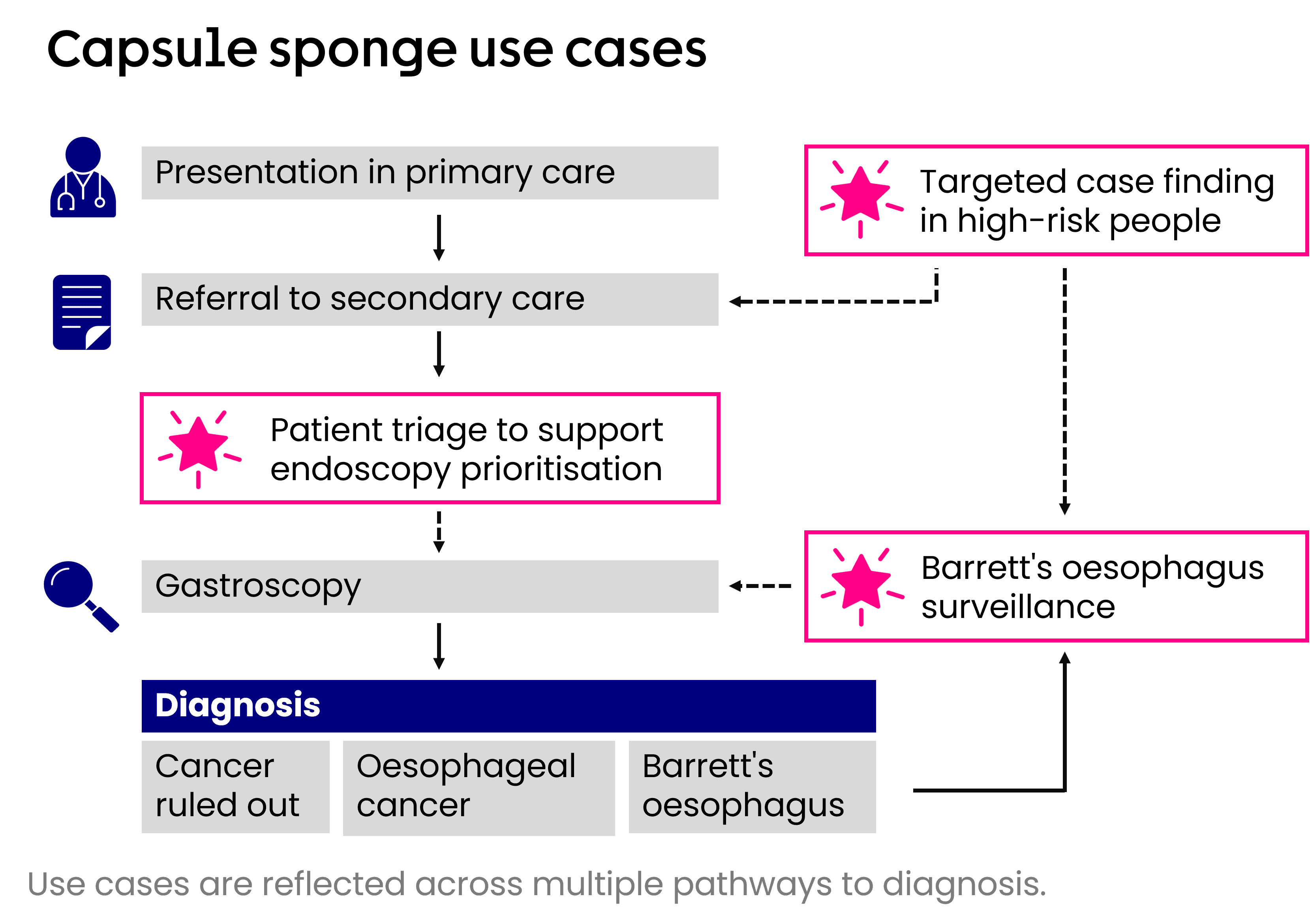

The capsule sponge test is being evaluated nationally in three different use cases:

Triaging patients with reflux symptoms waiting for gastroscopy in secondary care

Surveillance in people with Barrett’s oesophagus

Targeted or proactive case-finding of Barrett’s oesophagus in people at high risk in a primary or community care setting

The image below shows these applications of capsule sponge across the diagnostic pathway for oesophageal cancer.

Open the accordions below to find out more about different evaluations capsule sponge testing across the UK.

A range of activity is needed to support the implementation of capsule sponge testing into practice, as sufficient evidence becomes available.

Evaluations should be published in a timely manner and should outline clear recommendations, next steps and who is responsible to action those.

There is a need for clinical guidance to outline how capsule sponge testing could be integrated into health systems.

Further real-world data is required to evaluate capsule sponge testing in practice, focusing on how capsule sponge testing improves patient outcomes.

Further research to assess and compare different capsule sponge devices if needed, to reduce the potential risk of bias in existing studies.

Capsule sponge testing is being rolled out across all health boards in Scotland. There isn’t a pathway for capsule sponge implementation yet in Wales and Northern Ireland.

In England, there’s no national funding stream for capsule sponge testing, but funding is available to support Cancer Alliances to integrate capsule sponge into their service. NHS Trusts can work with their local Cancer Alliance to write a business case and explore funding options. Guidance is available on Future NHS.

In all nations, health systems can take the following steps to prepare and ensure that future activity is successful:

Ensure clinicians are fully informed of any changes to pathways.

Ensure that referral forms include capsule sponge if available.

Capsule sponge results should be integrated in Electronic Health Records.

Consider the required estates and equipment to integrate alternative diagnostics.

Provide clinical guidance to support practice.

Continued local and national evaluation of the intervention to ensure best practice is implemented.

Health systems should also engage with each other to share learnings to ensure implementation is effective.

Evidence is emerging to assess how Artificial Intelligence (AI) deep-learning models might be used in analysis of samples collected during capsule sponge testing. AI has the potential to support pathology services by reducing demand on the workforce and improving efficiency

, , , . Further research is required to assess the appropriate role/s AI could play in the detection of Barrett’s oesophagus and oesophageal cancer.Newsletters targeted at health professionals which provide intelligence to support evidence-based decision making and updates on our activities, as well as our bespoke GP newsletter which includes best practice guidance, practical tools and expert resources.

See the range and sign up

Kadri SR, et al. Acceptability and accuracy of a non-endoscopic screening test for Barrett’s oesophagus in primary care: cohort study. BMJ. 2010 Jan 25;341(sep10 1):c4372–2.

Fitzgerald RC, et al. Cytosponge-trefoil factor 3 versus usual care to identify Barrett’s oesophagus in a primary care setting: a multicentre, pragmatic, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet [Internet]. 2020 Aug 1;396(10247):333–44.

Ross-Innes CS, et al. Evaluation of a Minimally Invasive Cell Sampling Device Coupled with Assessment of Trefoil Factor 3 Expression for Diagnosing Barrett’s Esophagus: A Multi-Center Case–Control Study. Franco EL, editor. PLOS Medicine. 2015 Jan 29;12(1):e1001780

di Pietro M and Fitzgerald RC. Revised British Society of Gastroenterology recommendation on the diagnosis and management of Barrett’s oesophagus with low-grade dysplasia. Gut. 2017 Apr 7;67(2):392–3.

Barrett's oesophagus and stage 1 oesophageal adenocarcinoma: monitoring and management, NICE, 2023. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng231

Diagnosis and management of Barrett esophagus: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline, 2023. https://www.bsg.org.uk/getmedia/88cfdd3f-2593-4cd5-bb9a-ff1c1d4e0c61/ESGE-Barretts-Guideline.pdf?ext=.pdf(PDF)

Chien S, et al. Oesophageal cell collection device and biomarker testing to identify high-risk Barrett's patients requiring endoscopic investigation. Br J Surg. 2024 May 3;111(5):znae117.

Chien S, et al. CytoSCOT group. National adoption of an esophageal cell collection device for Barrett's esophagus surveillance: impact on delay to investigation and pathological findings. Dis Esophagus. 2024 Apr 27;37(5):doae002.

Bouzid K, et al. Enabling large-scale screening of Barrett’s esophagus using weakly supervised deep learning in histopathology. Nature Communications [Internet]. 2024 Mar 11 [cited 2024 Mar 21];15:2026.

Gehrung M, et al. Triage-driven diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus for early detection of esophageal adenocarcinoma using deep learning. Nat Med 27, 833–841 (2021).

Pilonis ND, et al. 2022 Use of a Cytosponge biomarker panel to prioritise endoscopic Barrett's oesophagus surveillance: a cross-sectional study followed by a real-world prospective pilot Lancet Oncoloy Vol:23: 2, p270-278

Berman, A.G., et al. (2022). Quantification of TFF3 expression from a non-endoscopic device predicts clinically relevant Barrett’s oesophagus by machine learning. eBioMedicine, 82, p.104160.