Treatment

Your child might have radiotherapy to:

the area where the tumour was (if it’s been removed with surgery)

the tumour itself

to the whole brain or spinal cord

Radiotherapy might be your child’s main treatment if they have a brain tumour that is not suitable for surgery.

Or they might have radiotherapy after surgery to:

treat any tumour that their surgeon couldn't remove

try to lower the risk of the brain tumour coming back in the future

Some children have radiotherapy and chemotherapy together.

Your child’s specialist will usually avoid using radiotherapy to the whole brain and spine if your child is younger than 3. This is because they are more likely to develop long term side effects at this age.

Your child’s doctors might recommend chemotherapy instead of whole brain and spine radiotherapy. This aims to keep your child's tumour under control until they can have radiotherapy.

Some children under 3 have radiotherapy just to the area containing the tumour. This way, doctors can delay having radiotherapy to the whole brain and spinal cord until your child is older. Or, they might not need to have it.

Your child will have radiotherapy in small amounts (doses). You might hear these called fractions. Your child usually has one treatment a day, from Monday to Friday, for around 6 weeks. This means they have around 30 treatments, or fractions, of radiotherapy in total.

Some children might have 4 weeks of radiotherapy to their whole brain and spine. Then 2 weeks of treatment just to the area of the tumour.

How long and how much radiotherapy your child has depends on their type of brain or spinal cord tumour. Your child’s doctors will talk with you about the plan.

Your child might have radiotherapy to help with symptoms or slow down the growth of their tumour. This is called palliative radiotherapy and is usually a shorter course of treatment. This might be for around 2 weeks.

External radiotherapy uses specialised radiotherapy machines to aim radiation beams at a cancer. This is the type of radiotherapy most children have for a brain tumour.

The radiation beams destroy the cancer cells. There are many different types of external radiotherapy. The best one to use depends on the type of cancer and where the tumour is in the in the body.

The most common type of radiotherapy machine is called a linear accelerator machine (LINAC). This uses electricity to create the radiotherapy beams.

Many children have intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). IMRT is a type of conformal radiotherapy. Conformal radiotherapy shapes the radiation beams to closely fit the area of the cancer.

Your child can have IMRT on a standard radiotherapy machine, called a linear accelerator (LINAC).

The LINAC has a device called a multi leaf collimator. The multi leaf collimator is made up of thin leaves of lead which can move independently.

They can form shapes that fit precisely around the treatment area. The lead leaves can move while the machine moves around the child. This shapes the beam of radiation to the tumour as the machine rotates.

This means that the tumour receives a very high dose of radiotherapy and normal healthy cells nearby receives a much lower dose.

Each radiotherapy beam is divided into many small beamlets that can vary their intensity. This allows different doses of radiation to be given across the tumour.

IMRT can also create a U shaped (concave) area at the edge of the radiotherapy field. This avoids high radiation doses to structures that radiotherapy might otherwise damage. So IMRT can reduce the risk of long term side effects.

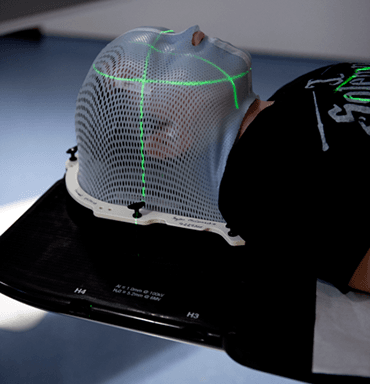

Your child’s head needs to be kept as still as possible during radiotherapy. This is so the treatment is as accurate as possible. Keeping the head still is called immobilisation. So, before your child’s treatment they have a mesh plastic mask made.

The play team will also explain and show them the radiotherapy room, they’ll also meet the radiotherapy team. Some play teams have a model to show your child what to expect and where they will be during treatment. By getting the play team involved it makes the whole experience a little less frightening for your child.

The mask is made to mould the shape of your child’s face. It covers the whole of their face and the front of their head.

This technique uses a special kind of plastic heated in warm water so that it becomes soft and pliable. The technician puts the plastic on to your child’s face so that it moulds to fit their face exactly. It feels a little like having a warm flannel put onto your face. Your child can still breathe easily, as the plastic won't cover their nose or mouth.

After a few minutes the mesh moulds becomes hard. The technician takes the mask off. It is then ready for use.

All of the radiotherapy team are used to treating children with cancer. They will do everything to make sure that your child is comfortable and prepared while the mask is being made.

The mask attaches to the scanner or radiotherapy machine bed while your child is wearing it. This means that they can't move, but there is nothing actually attached to them directly.

Some hospitals encourage children to paint and decorate their own radiotherapy masks.

Some very young children find it difficult to stay still and need to have a for their radiotherapy treatment. Many children do manage to lie still for the short amount of time each dose takes.

Your child’s play specialist will help and prepare them. They can make masks for your child’s teddy to show them what it looks like. They also provide good distractions and ways to keep calm, or occupied, during radiotherapy.

The Brain Tumour Charity have an animation for children to watch before having radiotherapy. It can help them feel more prepared knowing what to expect.

Before treatment your child has a planning CT scan. This scan helps the physicists plan the radiotherapy. They make a map of where the radiotherapy needs to go and finalise the dose of radiotherapy your child needs each day.

It’s likely your child will also have an MRI scan. They might have one at this stage, or the doctors might be able to use the pictures from any earlier MRI scans they have had.

Planning radiotherapy treatment generally takes 1 to 2 weeks.

Read about having an MRI scan or CT scan for children’s brain tumours

Radiotherapy machines are very big. They usually rotate around your child to give the treatment. The machine does not touch them at all.

The and play team explain what your child will see and hear. In some departments the treatment rooms have docks to plug in your own music player. Others have projectors, so children can watch programmes while having radiotherapy.

To have treatment your child lies on the treatment table. The radiographer attaches your child’s mask onto a board on the treatment table. Everyone leaves the room before their treatment starts.

Your child lies very still. The machine makes whirring and beeping sounds. It’s over quickly and they can't feel the radiotherapy when they are having the treatment.

Your child’s radiographers watch and listen to them on a CCTV screen in the next room. Ask the radiographers if you can go with them into the next room to watch and listen too. Your child can tell them if they need to move or want the machine to stop.

There may be a small delay while the radiographers take pictures of the tumour and compare them to the planning CT scan. The couch might move as they adjust their position.

You and your child might have to travel a long way each day for their radiotherapy, depending on where your nearest cancer centre is. This can make you and your child very tired, especially I they have side effects from the treatment.

You can ask the therapy radiographers for an appointment time that you think would better suit your child. They will do their best, but some departments might be very busy. Some radiotherapy departments are open from 7am till 9pm.

Car parking can be difficult at hospitals. You can ask the radiotherapy staff if they can give you a hospital parking permit for free parking or advice on discounted parking. They may be able to give you tips on free places to park nearby.

The radiotherapy staff may be able to arrange transport if you and your child have no other way to get to the hospital. Your child’s radiotherapy doctor would have to agree. This is because it is only for people that would struggle using public transport and have no access to a car.

Some people are able to claim back a refund for healthcare travel costs. This is based on the type of appointment and whether you claim certain benefits. Ask the radiotherapy staff for more information about this.

Some hospitals have their own drivers and local charities might offer hospital transport. So do ask if any help is available in your area.

Some children remain well enough during their radiotherapy treatment to keep going to school. Having radiotherapy doesn’t make them radioactive. It's safe for them to be with other people throughout their course of treatment. This includes pregnant women, their siblings and school friends.

Your child’s clinical nurse specialist can liaise with their school to talk about the treatment your child is having and how your child might feel. They can help support and educate the school to better support your child.

There are immediate and longer term side effects of radiotherapy.

Immediate aide effects tend to start a few days after the radiotherapy begins. They gradually get worse during the treatment and for a couple of weeks after the treatment ends. But they usually begin to improve after around 2 weeks or so.

Long term side effects might develop weeks, months or years after treatment has ended.

Every child is different, and the side effects vary. They might not have all of the side effects. Some children have only mild side effects, but for others the side effects are more severe.

Radiotherapy side effects will also depend on the type of radiotherapy your child has. As well as the area in the brain that is treated.

The doctors and nurses looking after your child do everything possible to prevent and treat any side effects that come up.

Some of these can include:

This is also known as raised intracranial pressure (ICP). It can happen due to inflammation of the tissue that has had radiotherapy. Symptoms might include:

a headache that is usually there when waking or if it wakes your child from their sleep

being sick

changes to their vision

changes to their behaviour or moods

seizures (fits)

problems with their strength, balance or coordination

problems with their posture

abnormal pupils

not being alert or able to wake up

When your child first starts radiotherapy they’re usually an inpatient to monitor for this possible change. Your child would usually have and urgent CT scan and treatment is usually steroids to help reduce the inflammation if there are signs of this.

Your child might feel very tired during radiotherapy treatment. It tends to get worse as the treatment goes on and then improves. Encourage your child to rest when they need to.

Various things can help your child to reduce tiredness and cope with it. Some research has shown that taking gentle exercise can give you more energy. There should be a physiotherapist at the hospital who can help. It's important to balance exercise with resting.

A rarer complication is somnolence syndrome or early delayed syndrome. This is extreme tiredness where children sleep nearly all the time. They might have other symptoms. For example, a worsening of their old symptoms or a poor appetite.

Somnolence usually starts 4 to 6 weeks after treatment has finished. Just when you they think they are getting over treatment, this can be challenging. But it passes in time.

Your child’s doctor might temporarily increase their dose of steroids to reduce somnolence syndrome.

Your child might feel sick at times. The team can give them some anti sickness medication.

Your child might lose their appetite while having treatment. Seeing a dietitian and making a plan can help.

Try writing down what your child eats over a few days and when they feel like eating. There might be a pattern that you hadn’t noticed. If they are hungrier in the morning, focus on this time to offer them their favourite breakfast.

It’s likely your child will have an area of redness and possibly sore skin in the treatment area. Creams can help soothe the area. Talk to your child’s doctor about this.

Hair loss only happens in the area of the head that is being treated. Your child usually only loses patches of hair where the radiation beams entered and left.

Your child might complain of headaches and be more sensitive to light and noise. Some children might not be able to communicate this, but as the parent or carer you’ll know they aren’t feeling very well due to their change in behaviour and mood.

It’s important to let the team know if they are getting headaches or if something is not quite right so they can give painkillers to help. Also, so they can monitor in case it is a sign of raised intracranial pressure in the skull.

The salivary glands might receive some radiotherapy during treatment. The salivary glands are where spit or saliva is made. This can cause them not to work properly and means that your child might get a dry mouth. It can make eating and chewing a problem for your child.

Let the nurse know if they are off their food or complaining their mouth is dry. The doctor can prescribe lozenges, gels or sprays to help with this.

Younger children are more sensitive to radiotherapy. Because of this, and how much they are growing and learning, they are more likely to get long term side effects. Your child’s specialist team look at the benefits and risks of the treatment options available before deciding on radiotherapy.

Research is continuing to learn more about the risks of treatment side effects.

Some of the possible long term side effects include:

physical problems such as limb movement or weakness

growth problems

problems with learning and school work

hormone deficiency – which might lead to problems with puberty or fertility

a small risk of second tumours later in life

increased risk of stroke due to narrowing of the blood vessels in the area that was treated - symptoms include numbness or weakness on one side of your body, difficulty talking, headache or dizziness

clouding of the eye lens (cataracts)

Find detailed information about late effects and what can help

Proton beam therapy is a type of radiotherapy.

It uses protons rather than high-energy x-rays to kill cancer cells. Protons are tiny particles from the centre of atoms. They produce a sudden burst of energy when they stop, which stays inside the tumour. This means there is less damage to healthy cells around the tumour.

Proton beam therapy has been shown to work well for some children’s brain tumours. This includes for some children with low grade astrocytoma and some, but not all children with an ependymoma.

Your child’s specialist will talk with you if they think proton therapy might be beneficial for your child. They take into account any risks of travelling abroad for your child. And if there is a risk involved in delaying treatment.

There are 2 therapy centres in the UK and these are at:

The Christie Hospital in Manchester

University College London Hospital

University College London Hospital opened in 2021 so are gradually opening their service to the rest of the UK.

At the moment, some children needing this service might need to travel to one of these hospitals or abroad for proton beam therapy.

Last reviewed: 19 Dec 2022

Next review due: 19 Dec 2025

The main treatments for children’s brain and spinal cord tumours are surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy.

Chemotherapy uses anti cancer (cytotoxic) drugs to destroy cancer cells. Chemotherapy can work well for some types of brain tumour. Find out when they might have it, the drugs used, how they have it and the side effects.

Surgery is a common treatment for a brain tumour. Find out why your child has surgery, who does it and other information.

Brain tumours and their treatment can cause physical and mental changes. Understanding about what they might be can help you cope.

Proton beam therapy is a type of radiotherapy treatment. It uses high energy or low energy proton beams to treat cancer.

It is essential that parents and other close family have support. Find out what is availble and who can help.

About Cancer generously supported by Dangoor Education since 2010. Learn more about Dangoor Education

Search our clinical trials database for all cancer trials and studies recruiting in the UK.

Connect with other people affected by cancer and share your experiences.

Questions about cancer? Call freephone 0808 800 40 40 from 9 to 5 - Monday to Friday. Alternatively, you can email us.